Social media is a significant aspect of daily life for most of us. Almost all adult internet users use some form of online communication platform.[1]

Most social media services require users to share some of their personal data when they sign up. While most people have a general awareness that platforms collect user data, many users have only a vague understanding of the specific data captured and how it is used.[2],[3],[4],[5] How many of us can really say that we fully understand where and how our data is used online?

Building on our previous qualitative research and online trials, we wanted to test whether presenting information about data sharing in different ways improved internet users’ understanding of:

- what data was being collected

- the people and organisations who would have access to the data

- how the data would be used.

To do this, BIT and Ofcom ran an online trial which looked at two aspects of how information about data sharing could be presented:

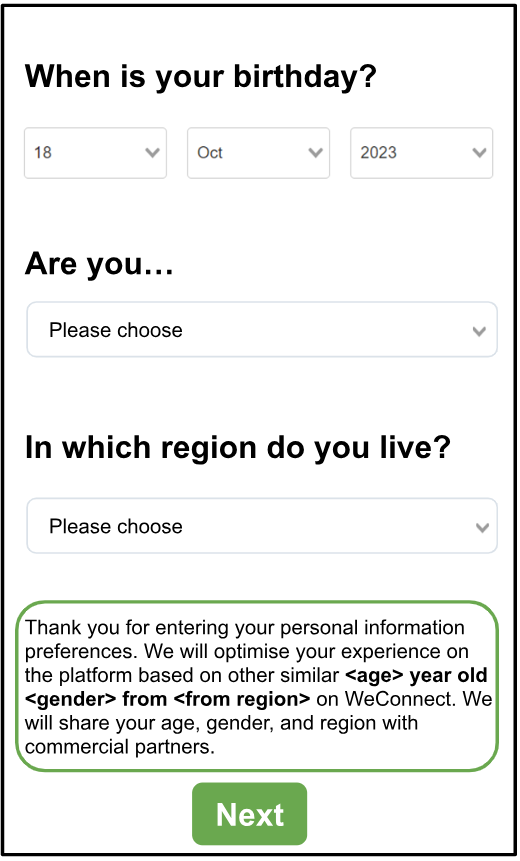

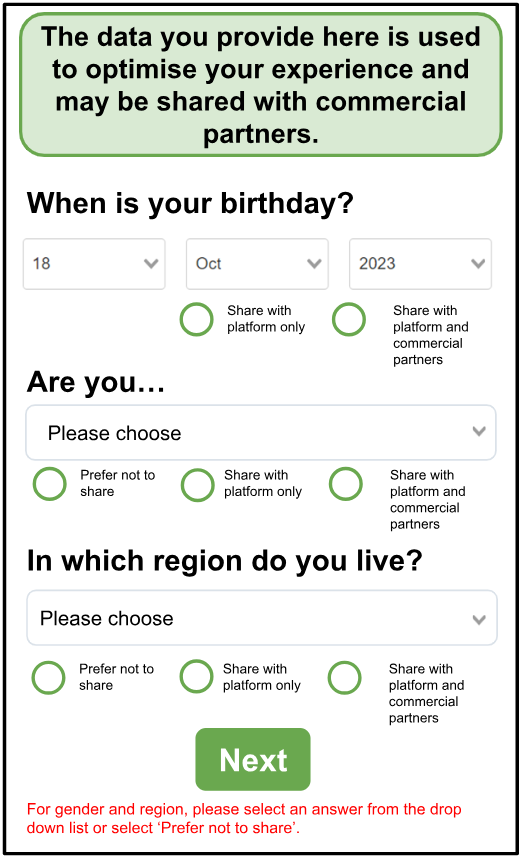

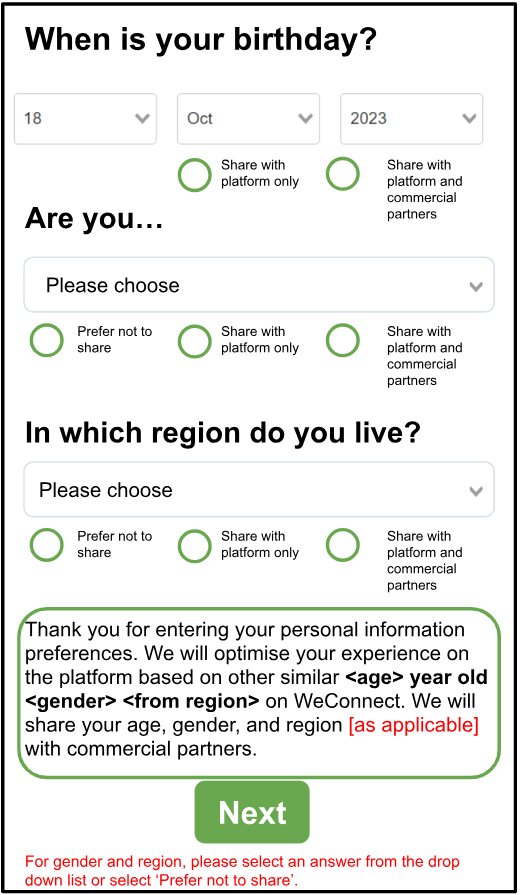

Messaging: information about data sharing could be made more obvious on the screen (“info salience”) or the implications of sharing the data could be set out with examples (“implications”).

Choice: users could be given the option to select which data to share, and with whom (“granular choice[6]”) or be required to share all information requested to access the platform (“no granular choice”).

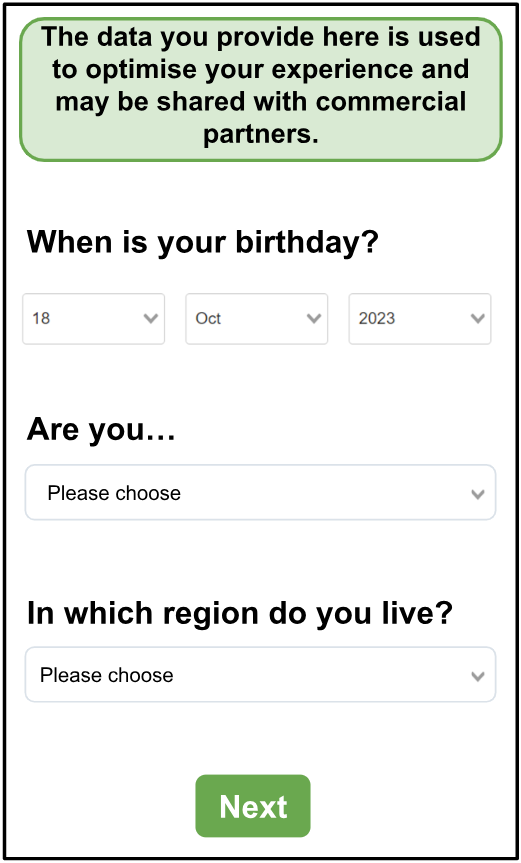

This resulted in four trial conditions, or ‘arms’, testing the different combinations of interventions, plus a control designed to replicate how existing social media platforms gather user data.

We had a sample of just over 7,000 UK adult internet users (i.e. ~1,400 per arm). Below, you can see screenshots of the four ‘arms’ that we tested, as well as the control.

Figure 1: Data collection screens for each of the trial arms, and the control.

How did the different ways of presenting information affect comprehension?

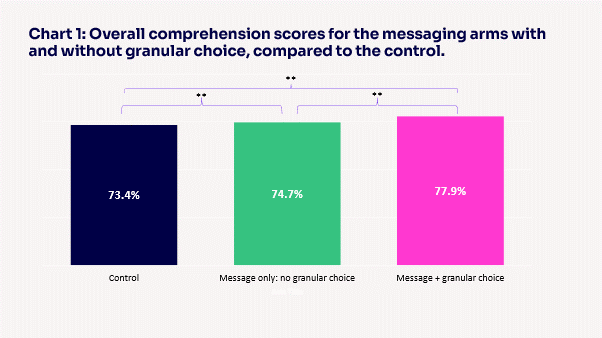

Overall comprehension[7] in the control arm was high at around 73%, indicating that participants had a generally high understanding of where and how their data was used. (This may reflect the fact that the research was conducted using an online panel, who may be more familiar with social media platforms than the general population.) Exposure to either of the ‘messaging’ arms increased overall comprehension by a small amount (around 1 percentage point). Being given the option to choose which data to share, and with whom, boosted participants’ overall comprehension by an additional 3.5 percentage points from the control level. These increases may seem small, but they are statistically significant.

Note: **statistically significant at the 1% level (p<0.01)

We saw a similar pattern when we looked at the different aspects of comprehension. Participants were more likely to better understand what data was being collected, the organisations who would have access to the data and how the data would be used, when the message was presented together with the option to choose which data to share, and again these differences were statistically significant.

Table 1: Mean scores for different aspects of comprehension for the messaging arms with and without granular choice, compared to the control.

| Mean comprehnsion scores (%) | Control | Message without granular choice | Message with granular choice |

|---|---|---|---|

| What data is collected | 75.3 | 75.8 | 77.6 |

| Who would have access to the data | 72.5 | 73.9 | 81.2 |

| How the data would be used | 70.1 | 72.9 | 74.5 |

How did the way information was presented influence data sharing choices?

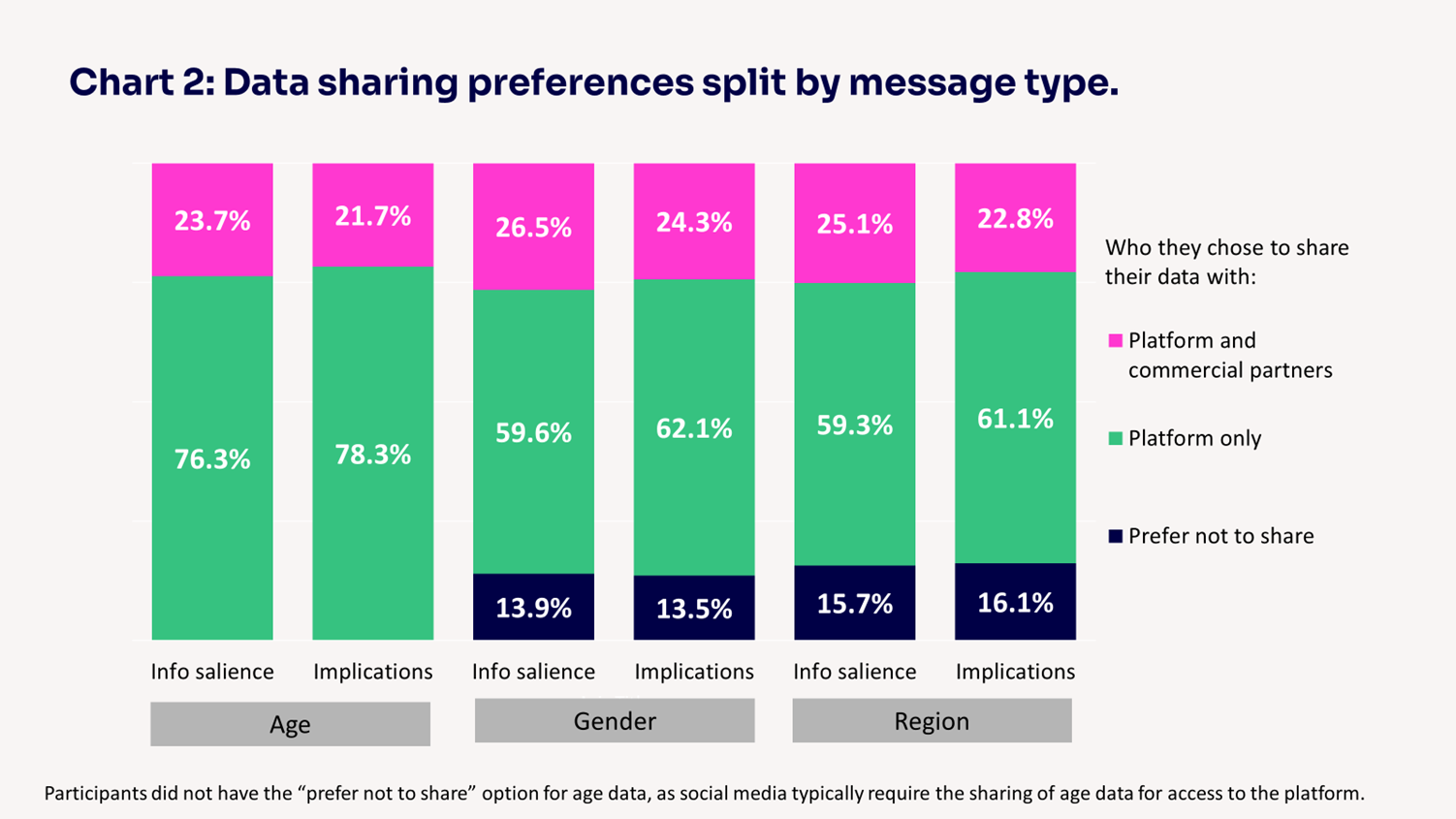

Six in ten participants chose to share their data with the platform provider only when given the option. Between a quarter and a fifth chose to share their data with commercial partners. The type of message that participants saw did not affect their data-sharing preferences – you can see from chart 2 below that data sharing was very similar regardless of whether participants were shown salient information, or whether the implications of data sharing were spelt out.

Nearly all participants who saw the implications message with the option to choose which data to share changed their sharing permissions and preferred not to share at least some of their data with commercial partners. Sharing information about their location (which in this trial was described as the region in which they lived) was particularly influenced by the implications message, with 84.3% changing it at least once. Interestingly, some participants also opted to change the region from the one they were in to another one - even though the data was at the regional level rather than a specific address or postcode.

Participants who chose not to share their data tended to say that this was because they valued their privacy (53%), wanted to be in control of their data (47%) or wanted to reduce the risk of identity theft (34%). Interestingly, despite knowing that they were taking part in an experiment, the participants were interacting with the process in what appears to be a realistic way.

How did people feel about the ways the information was presented?

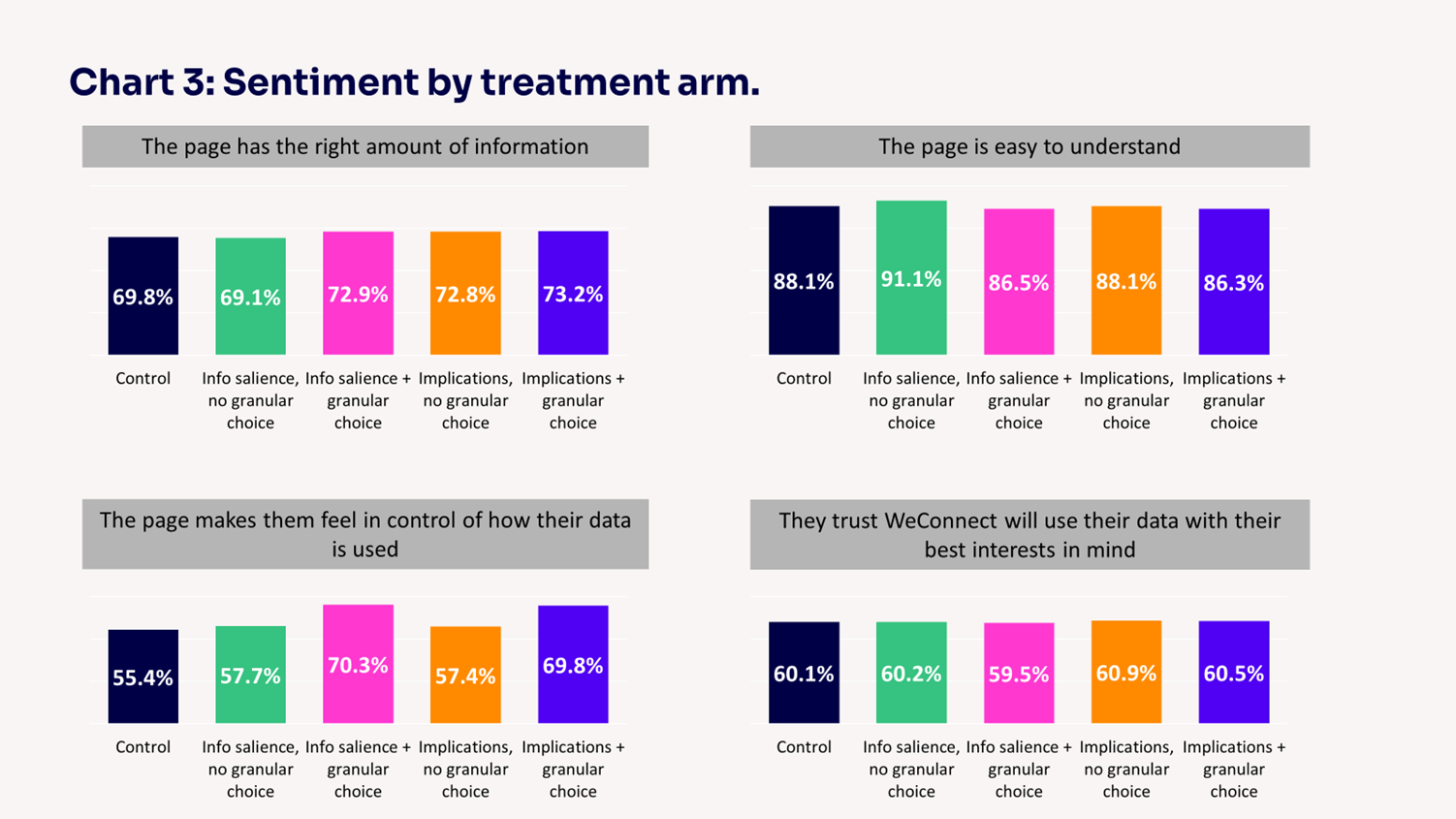

In general, the presentation of information in the trial arms was received more positively than the control arm. As Chart 3 illustrates, being given the option to choose which data to share made participants feel more in control of how their data was being used. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the levels of trust across all arms.

Were there any differences between demographic groups?

We were interested to see whether there were any differences in the findings by age, gender or social grade. Responses were broadly similar across different groups, with some minor exceptions. For those aged 25-44 and those in social grade AB, being presented with salient information was more effective than being shown the implications. Women had slightly better overall comprehension than men across all arms.

Were there any downsides to presenting the information in new ways?

There could be potential downsides to presenting data sharing information in a granular way, as users may feel there is too much information, or that the process has become too complex or time-consuming. The sentiment analysis in Chart 3 above shows that the majority did feel that they were given the right amount of information across all of the arms. However, we noted that participants who were given the option to choose which data they shared were more likely to drop out of the trial. While this didn’t impact the findings, it may suggest that the additional friction could have a real-world impact on motivations to sign-up to a platform. That said, our findings should be viewed in the context of an experiment, and in the real world, there will be other motivating factors (such as a desire to connect with friends) which could offset this effect.

What’s next?

We’ve seen that giving people the option to decide which data to share improves understanding by a small but significant amount. We have also seen that most people chose to share with the platform only, rather than commercial partners, when given the choice and that having this option makes people feel more in control.

You can read more detail about the trial and the results here.

This trial is the latest in a programme of online trials that Ofcom has run over the last two years which has looked at different aspects of users’ online behaviour and their interaction with different types of safety measures. The results from this trial will add to the evidence Ofcom collects on ‘what works’ to improve people’s online skills, knowledge and understanding as part of our Making Sense of Media Programme. You can read about how this trial fits with our wider work in our 3-year media literacy strategy.

Notes:

[1] Adults’ Media use and attitudes report 2024 (ofcom.org.uk)

[2] Rader, E. (2014). Awareness of behavioural tracking and information privacy concern in Facebook and Google. In 10th Symposium On Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2014) (pp. 51-67).

[3] Hope, A., Schwaba, T., & Piper, A. M. (2014, April). Understanding digital and material social communications for older adults. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 3903-3912.

[4] Pangrazio, L., & Selwyn, N. (2018). “It’s not like it’s life or death or whatever”: Young people’s understandings of social media data. Social Media+ Society, 4(3).

[5] Ofcom (2022) A Day in the Life (ofcom.org.uk)

[6] The “granular choice” option is not usually offered by social media platforms: if you think about the last time you signed up for a service, it’s likely that you had the choice to either accept the terms and share your data, or not to use the platform.

[7] ‘We measured comprehension across three measures: (i) what data was being collected (ii) the people and organisations with whom the data would be shared and (iii) how the data would be used. ‘Overall comprehension’ was a derived score across all of these measures.